Conflicted Legacy

The legacy of The March is marked by responses that contradict. The United States Information Agency Advisory Committee found the film deeply flawed and recommended that it should not be released. In stark contrast, USIA Director Edward R. Murrow called it the “finest petition for redress of grievance that has ever been put on film.”[1] Below you can explore a variety of responses to The March, including those offered by several agencies of the federal government, James Blue’s own defense of the film, and the opinions of the national media, film critics, and academics.

- The federal government’s response to The March (1964-1965)

- James Blue’s response to the USIA Advisory Committee criticism (February 1964)

- Newspaper editorials debate The March (1964-1965)

- Film criticism of The March (1964-1965)

- Contemporary academic interpretations of The March

- Conclusion

Stragglers soak their feet after the March on Washington. Still from The March by James Blue (1964).

The federal government’s response to The March

The United States Information Agency (USIA) intended The March to serve as as a weapon in the global Cold War. Edward R. Murrow, the director of the USIA when the documentary was commissioned, believed that the ideals of free speech and petition should be celebrated, and that they would diminish the appeal of communism. The USIA Advisory Committee and its chair Clark Mollenhoff disagreed with Murrow’s assessment, as did conservative senators. President Johnson had problems with the film, as the transcripts of his conversations reveal.

President Johnson’s response to The March

President Johnson thought the film should celebrate the actions taken by his and John F. Kennedy’s administration. You can listen to the exchanges he had with his staff and senators about The March on LBJ’s “Difficult Problem.”

The USIA Advisory Committee’s response to The March

United States Information Agency Advisory Committee unanimously recommended against showing the film. Committee chair Clark Mollenhoff was agitated by the film, finding it to be a thoroughly negative depiction of America’s race problem.

The USIA’s Response to the Criticism of The March

United States Information Agency Directors Edward R. Murrow and Carl Rowan defended the film.

The Legislative Branch

Senators from Southern states also did not like the film. They thought it aired America’s “dirty laundry” to the world, damaging the US effort to counter the Soviet Union in the global Cold War.

James Blue's Response

"'We Have Told the World' (James Blue's defense of The March)," James Blue papers, Coll 458, Box 83, Folder 22, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, Oregon. Copyright Richard Blue. Reproduced with permission.In response to the criticisms of the USIA Advisory Committee, James Blue crafted a thoughtful defense of his film on the basis of its truthfulness to democratic ideals. Only a totalitarian state, he wrote, would produce a documentary of a protest that portrayed the government in a perfectly positive light. By showing the negative side of American racism along with the positive side of peaceful protest, Blue believed that his film would tell the world an authentic story of American democracy in action.

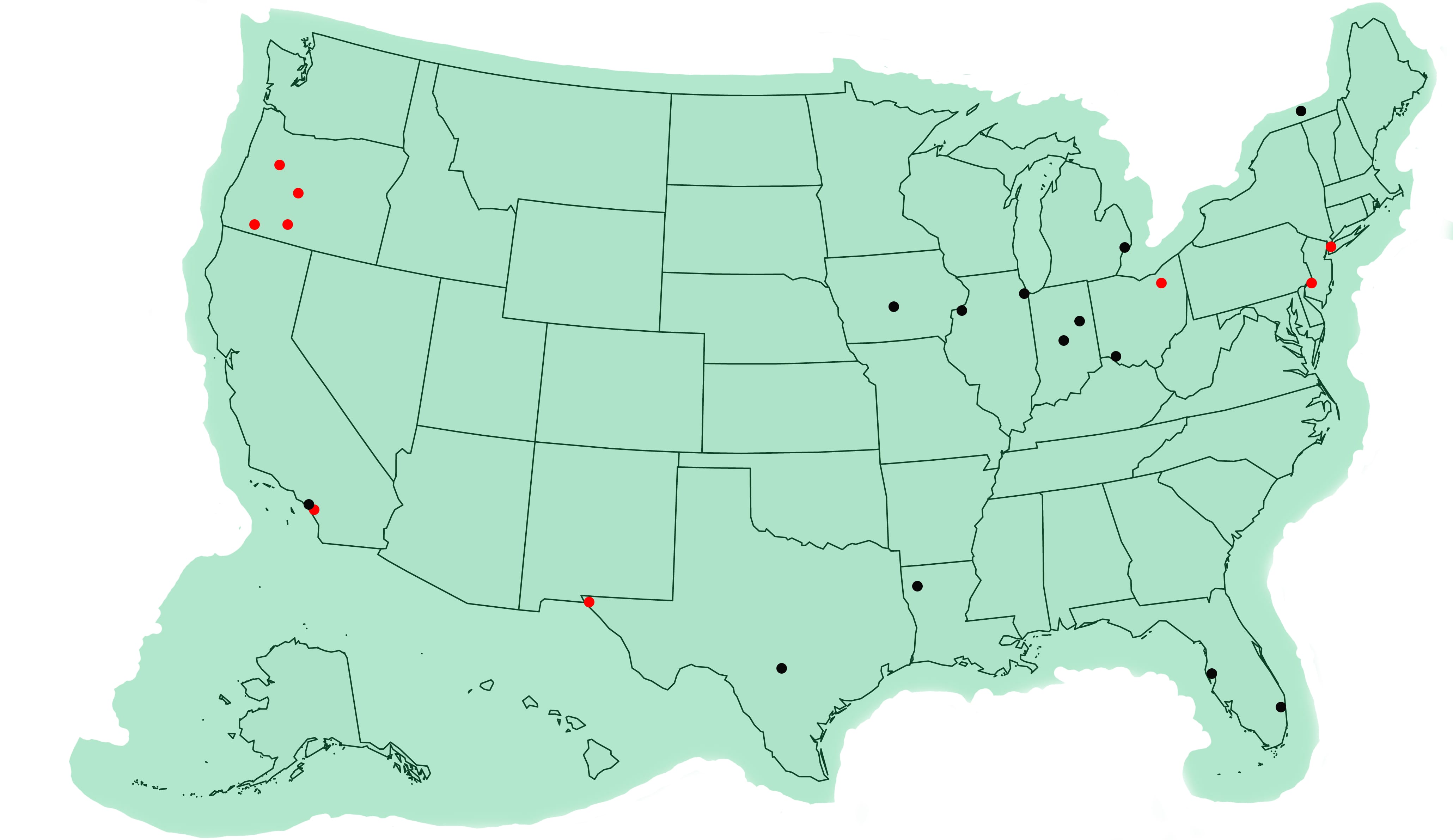

Black dots indicate an article about James Blue’s The March, while red dots indicate an article about the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Map by Tom Fischer, 2018.

Film criticism of The March (1964-1965)

A number of film critics at the time praised The March for its graceful and subtle depiction of a “day of hope.” The film won First Prize for Human Relations at the Venice Documentary Festival (1963); Grand Prize in Documentary at the International Ibero-American and Philippine Film festival in Bilbao, Spain (1964); a Diploma of Merit at the 14th Melbourne Festival in Australia (1965); First Prize at the Cannes Youth Festival (1966) and First Prize at the Netherlands Film Festival (1966). Arthur Schlesinger Jr., one of the reigning historians and film critics of the era, wrote that “James Blue, a young and gifted film maker … has made [with The March] what will surely go down as one of the great documentaries.”[2]

Contemporary academic interpretations of The March

Contemporary critics admire the artistic expressions in the film but believe the film is ahistorical, holding that it depicts interracial harmony as a norm and that it airbrushes and sanitizes the conflicts within the Civil Rights Movement and the intransigence of the Kennedy administration.

Tony Shaw, in his book Hollywood’s Cold War, captures an informed judgment on the film from a vantage point some 45 years after the debut of The March:

Yet, however authentic the film would have appeared to most viewers, Blue’s choices of focus told the story of this seminal event from a perspective that highly favoured the US government. Peace, consensus and a sense of progress shone throughout. Conflict, both between the civil rights protestors and the Kennedy administration, and within the civil rights movement itself over goals and tactics, was airbrushed out. The forward-looking ‘dream’ parts of King’s speech were included, but not those in which he had criticised the US Constitution for letting down African-Americans. The film’s overall impression was that of a united, respectful, interracial movement enjoying the fruits of liberty, and carrying out the democratic ideals of free speech and political participation.[3]

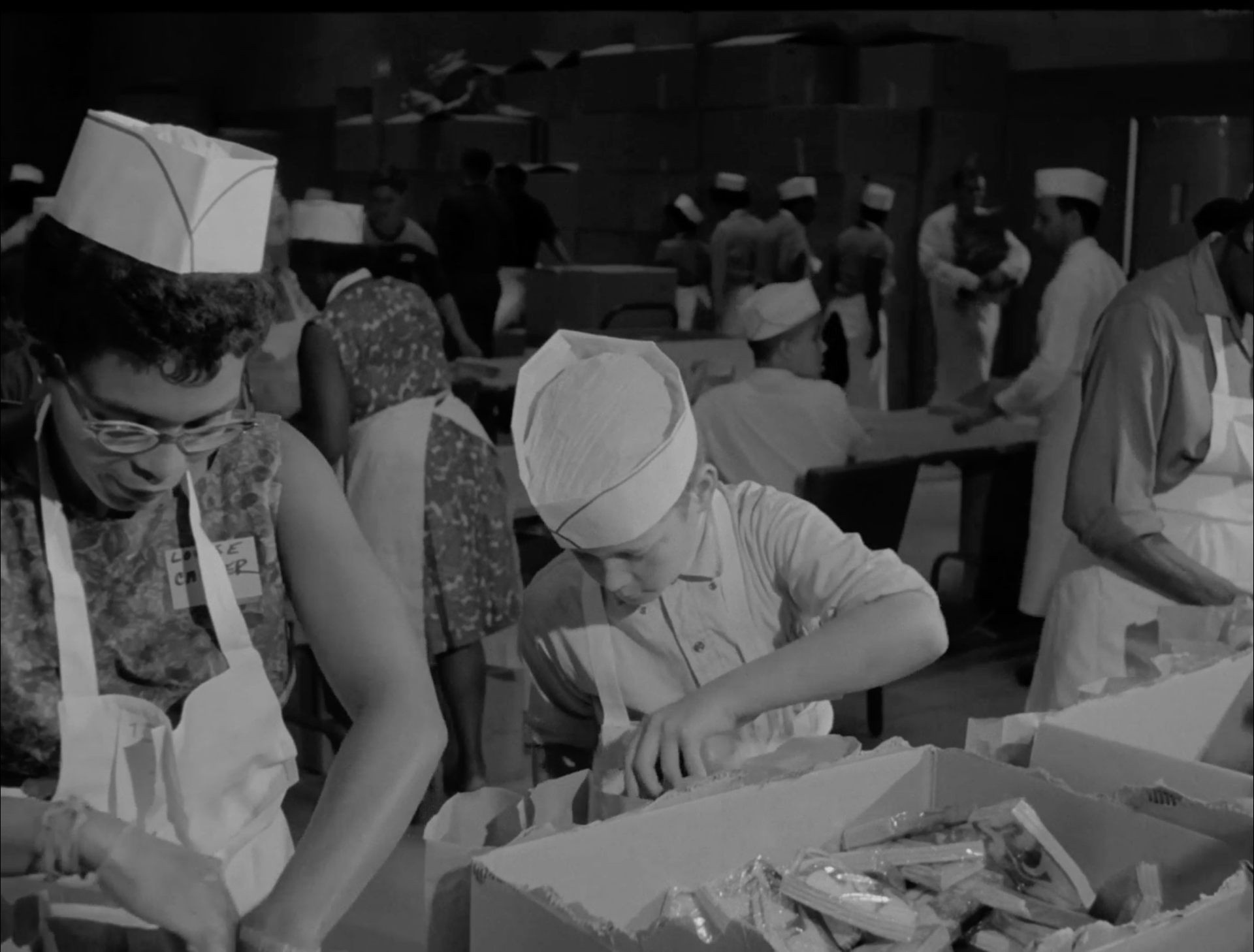

Volunteers prepare bagged lunches in New York in preparation for the March on Washington. Still from The March by James Blue (1964).

Conclusion

The charges against the film made by critics come come from two opposing sources: conservatives who argued that Blue was airing America’s “dirty laundry” and progressives (mostly modern day) who claim Blue “sanitized” American racism by featuring interracial collaboration in his film. This digital exhibition aims to show that that James Blue’s The March eloquently weaves two forces in American history, the contradictions of racism and anti-racism, into a humanistic and poetic documentary of the August 28, 1963, March on Washington.