Reactions in the News

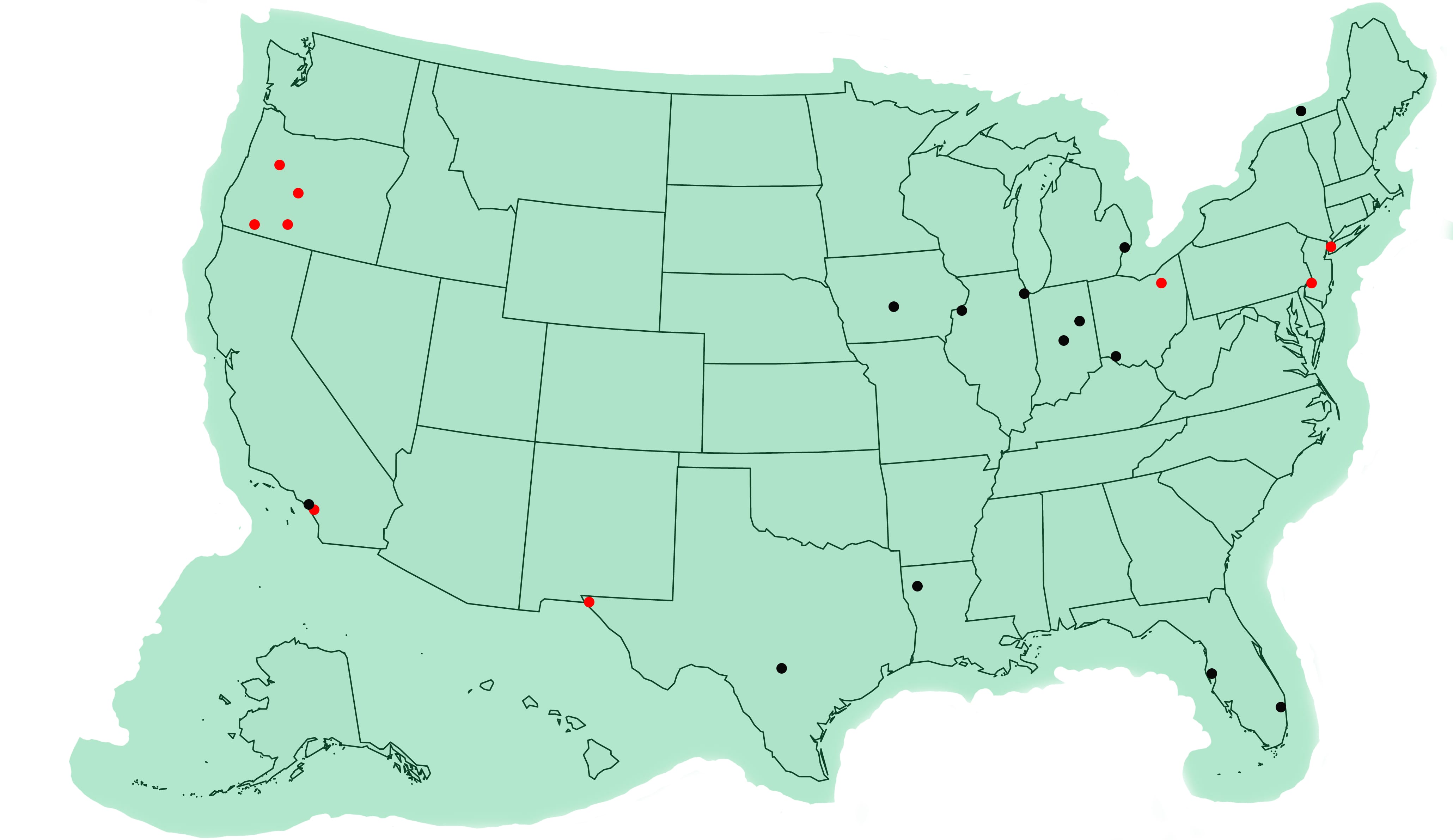

Black dots indicate an article about James Blue’s The March while red dots indicate an article about the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Map by Tom Fischer, 2018.

The March in the News

General Consensus

Unsurprisingly, the March on Washington caught a great deal of media attention, not all of it laudatory. By and large, however, papers and journalists with a variety of political stances expressed their approval of how the March was conducted: The New York Times editors declared that “Without violence, the march on Washington was the greatest assembly for redress of grievances in the capital’s history…”,[1] while Vincent S. Jones of the Camden Courier Post noted that “The [Courier-Post] editors split, to some extent, over the Aug. 28 March on Washington.

Few thought that it would do any good. Most doubted the wisdom of the demonstration. All praised the way it was carried out.”[2]

These reserved praises come after a great deal of nail-biting from some journalists: the AP declared of the March that “The atmosphere turned out to be part carnival, part political rally, part revival and part plain old curious. Although this was labeled as a protest march, for better jobs, for housing, for freedom the gathering was surprisingly good humored and exuberant,”[3] while the UPI underscored the potential dangers of the day, stating that:

All the ingredients were there. Two hundred thousand persons were in a highly emotional state. Many had gone without sleep. The sun was hot, it was difficult to get a drink of water or a sandwich.

And, lurking on the fringes of the march were people and organizations who did not want the demonstration to be peaceful and orderly. They knew–and so did the leaders of the march–that a sudden burst of temper could be a spark that would ignite a bonfire that could become a holcause [sic].[4]

Efficacy

Some questioned the impact of the March. The LA Times reported that Sens. Strom Thurmond (D-SC) and Everett Dirksen (R-IL) stated that the March would not garner votes for the upcoming civil rights legislation, and indeed would not change any minds at all.[5] Sen. Hubert Humphrey (D-MN) is alternately reported as saying the March would not have any real effect in the Senate (NYT) or that it would have a large one (LAT). Journalist William S. White complained that marching techniques smelled strongly of fascism and communism, stating that “This columnist makes no suggestion that what is involved here is a ‘Communist plot’…however, this essential point remains: the massive and interminable street marching [civil rights leader Bayard] Rustin and others are now proposing is strictly within the operating tradition of the Communist and Fascist marching movements.”[6] An editorial some years down the road in the El Paso Herald-Post bemoaned the widespread use of disruptive protest tactics,

Negroes who contend that they have serious grievances against present day American society surely are not going to limit themselves to doing things which do not disturb the white elements of the national community. But they may now decide that other approaches may prove more productive than street demonstrations…

The Negroes can hardly outdo what they have done. They should at this moment have rounded some kind of corner. The should be entering upon a new and sober course in which they may realize that if they are to demand privilege and opportunity, they must offer duty, discipline and high responsibility in return.[8]

Jobs

Of course, there were other angles of criticism for the March. One writer in the Oberlin Activist complained that the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, or at least the discussion surrounding it, had completely ignored half of its program:

The moral tone to the Civil Rights demonstrations has almost obscured the word “Jobs” which was, originally, part of the demonstrators’ program. Who connects economic legislation with opposition to Wallace or Barnett? Who suggests that violence in Birmingham and social policy may be correlated? Too many questions have simply been forgotten. The mass following for the Civil Rights movement is not unconnected to unemployment and the rediscovery of the old truth that negroes are “first fired and last hired.” The demonstrations attracted bigger crowds in Detroit than in Washington…[9]

These economic concerns were echoed by a Del Varela in the Carta Editorial of Los Angeles, but the writer has a different view of the efficacy of the March’s economic platform:

The March marked a basic switch in the civil rights struggle, for it broadened, as it must, into the areas of full employment and social welfare that directly affect the whole country. This switch in emphasis is reflected in the demands of a massive retraining program for all the unemployed, a $2.00 national minimum wage, and an improved fair labor standards act.

The march was evidently not a culmination, but a new beginning of what will be a gigantic national readjustment.[10]

Dignity

Regardless of questions of efficacy, one editor of the Medford, Oregon, Mail Tribune apologized for earlier criticisms of the March, quoting Oregon Senator Maurine Neuberger in evaluating some inessential benefits that came of it: “Perhaps [the question of efficacy] is irrelevant; perhaps the more relevant question might be what the demonstration has done to and for the participants themselves, in terms of self-confidence, determination, human dignity, and self-respect.”[11]

James Blue’s The March in the News

As Propaganda

Just as the March itself was a big topic in the news, James Blue’s The March would also have its day in the sun. While some criticism of the film comes from its construction as a film, in the United States it became a frequent source of complaints around the time of Carl Rowan’s confirmation hearing.

Allan H. Ryskind of the Indianapolis News, allowed to view the film by the United States Information Agency despite the general prohibition on showing USIA films on American soil, describes his thoughts on the 30-minute documentary:

This reporter was allowed by USIA officials to view the film and make his own decision. The resulting conclusion is that distribution overseas would be seriously damaging to America’s image. Through 30 minutes of film clips, the viewer is inundated with the chants of 200,000 Negroes and whites crying “freedom, freedom” and demands that Negroes be entitled to earn a decent living. Major attention is devoted to Martin Luther King’s highly inflammatory rhetoric in which King talks of “unspeakable horrors” visited upon the Negro and the “vicious haters” in Alabama and Mississippi.

There is not a paragraph, sentence or syllable which alleviates King’s picture of harsh living conditions for the American Negro. There is no mention of the enormous progress Negroes have made in the United States.[12]

The Muncie, IN Star Press complained that, as always, “The United States Information Agency seems to go its traditionally inept way, no matter who is in the boss’ office, accentuating the negative about America.”

USIA’s mission is basically a positive one to promote the U.S. Some of its personnel seem confused about this and wish to be objective in the academic or journalistic style of modern realism, thinking that this would be more convincing in the untutored areas of the world.

This attitude does not impress congressmen favorably, nor does it seem to carry too much weight with an advisory commission made up of experts in the field.[14]

He fingers The March directly, noting that

The commission earlier sharply criticized the agency for distributing a film of the march on Washington for Negro equality in African countries where it would be misunderstood. This criticism was reinforced in the annual report warning the agency to avoid “questionable presentations of historic events which lead to domestic controversy.”[14]

Though the film was commissioned by Edward Murrow,

Reporters made note of Sen. Bourke B. Hickenlooper (R-IA) and his opposition to the film; Rowan used Hickenlooper’s comments as opportunities to clarify his own position on the film and what he would do as USIA director:

Here Hickenlooper turned to the “March on Washington” film. Hickenlooper didn’t like the movie. He thought it showed protesting Negroes without mentioning the advances they have made in this country. “I can imagine no propaganda weapon more effective in the hands of the Communists than that film,” he said.

Rowan had seen the film, and had liked it, although he said if he had been making it he would have included a shot of the leaders meeting affably with the President.[16]

Rowan noted that the film showed that “the Negro has freedom to protest…It counteracts the idea that Negroes are in continual battle with whites by showing whites and Negroes marching together.” He also notes that a large portion of the crowd was made up of well-dressed, middle-class black professionals, and that this was itself a sign of progress.[17]

As a Film

Of course, The March didn’t just catch the attention of pundits and senators. It also received largely favorable reviews from film critics overseas. John Gillett, writing for the Guardian noted that the film was one among several works that dealt with America’s racial problems playing at the Venice Film Festival of 1964:

Naturally, racial problems are uppermost in the minds of many American film-makers at the moment. “Nothing But a Man” gives a fictional account of the Negroes’ right to be treated as individual human beings whereas “The March” (directed by James Blue), about the recent march on Washington, achieves the difficult task of making mass emotions seem meaningful and is beautifully shot and edited into the bargain.[18]

‘The audience should not feel they are being sold a bill of goods. In a good film the point is explicit.’

‘In any case,’ Mr. Blue said, ‘things you discover yourself in a film are going to impress you much more than what you are led to believe.’[19]

She notes the controversy that The March stirred on Capitol Hill but doesn’t say much about the film itself, aside from its recent screening in Venice.

References

[1] New York Times, “News Summary and Index: The Major Events of the Day,” August 29, 1963.

[2] Jones, Vincent S. Courier-Post (Camden, NJ), “Negro Progress Shown—‘The Road to Integration’: Down-to-Earth Reporting,” November 28, 1963.

[3] STATESMAN JOURNAL (Salem, OR): FREEDOM MARCH HAS A GALA AIR (AP), August 29, 1963.

[4] BEND BULLETIN: GRIM GAMBLE SUCCEEDS–MARCH ON WASHINGTON COMES OFF WITHOUT VIOLENCE SOME FEARED (UPI), August 29, 1963.

[5] Los Angeles Times, The Nation—Civil Rights: A Message From 200,000 Marchers—What Was Gained?, August 29, 1963.

[6] White, William S. Los Angeles Times: Beware of Marching Techniques, September 5, 1963.

[7] Lee, Robert W. El Paso Herald-Post, “Key Word is ‘Peaceable,’” May 27, 1968.

[8] HERALD AND NEWS (Klamath Falls, OR): A NEW AND SOBER COURSE, September 11, 1963.

[9] Oberlin Activist, Fall 1963.

[10] Del Varela, Carta Editorial (LA), “March on Washington,” September 12, 1963.

[11] MEDFORD (Medford, OR) MAIL TRIBUNE: MARCH ON WASHINGTON, August 29, 1964.

[12] Ryskind, Allan H. Indianapolis News, “Senators Are Concerned: USIA ‘Rights’ Film Twists American Image Overseas,” February 29, 1964.

[13] The Star Press (Muncie, IN), “Look Who’s Selling Mob Action,” February 17, 1964

[14] Wilson, Richard. Des Moines Register, “U.S. ‘Not Putting Out Its Best Foot,’” February 9, 1964.

[15] San Antonio Express, “USIA’s Racial Coverage Defended” (AP), June 15, 1965.

[16] Edson, Arthur. Fort Lauderdale News, “Tough Job Ahead for Carl Rowan: USIA Boss Faces World with Truth” (AP), April 5, 1964.

[17] Moline Daily Dispatch, “Movies of the March,” February 29, 1964.

[18] Gillett, John. Guardian, “The Venice Film Festival,” September 8, 1964.