Field Guide to The March

James Blue’s minimal narration in The March disguises the fact that the film represents a rich array of people, places, and songs associated with the Civil Rights Movement. On this page, you can learn more about the sights and sounds of The March.

Characters

Landscapes

Music

Characters

James Blue (1930-1980), was an American filmmaker and alumnus of the University of Oregon. You can learn more details of his life and work in The Making of James Blue, or over at the James Blue Project.

Dr. Merritt Hedgeman was a prominent conductor of black folk music and opera. He directed music at Riverside Church in New York City. This coupled with his wife’s connections made him a natural choice to conduct the choir formed by the National Council of Churches. The choir sang for events in New York City leading up to the March on Washington. Hedgeman can be seen in The March conducting the group outside a sandwich-packing operation prior the demonstration.

Landscapes

On the road to Washington. Still from The March by James Blue (1964).

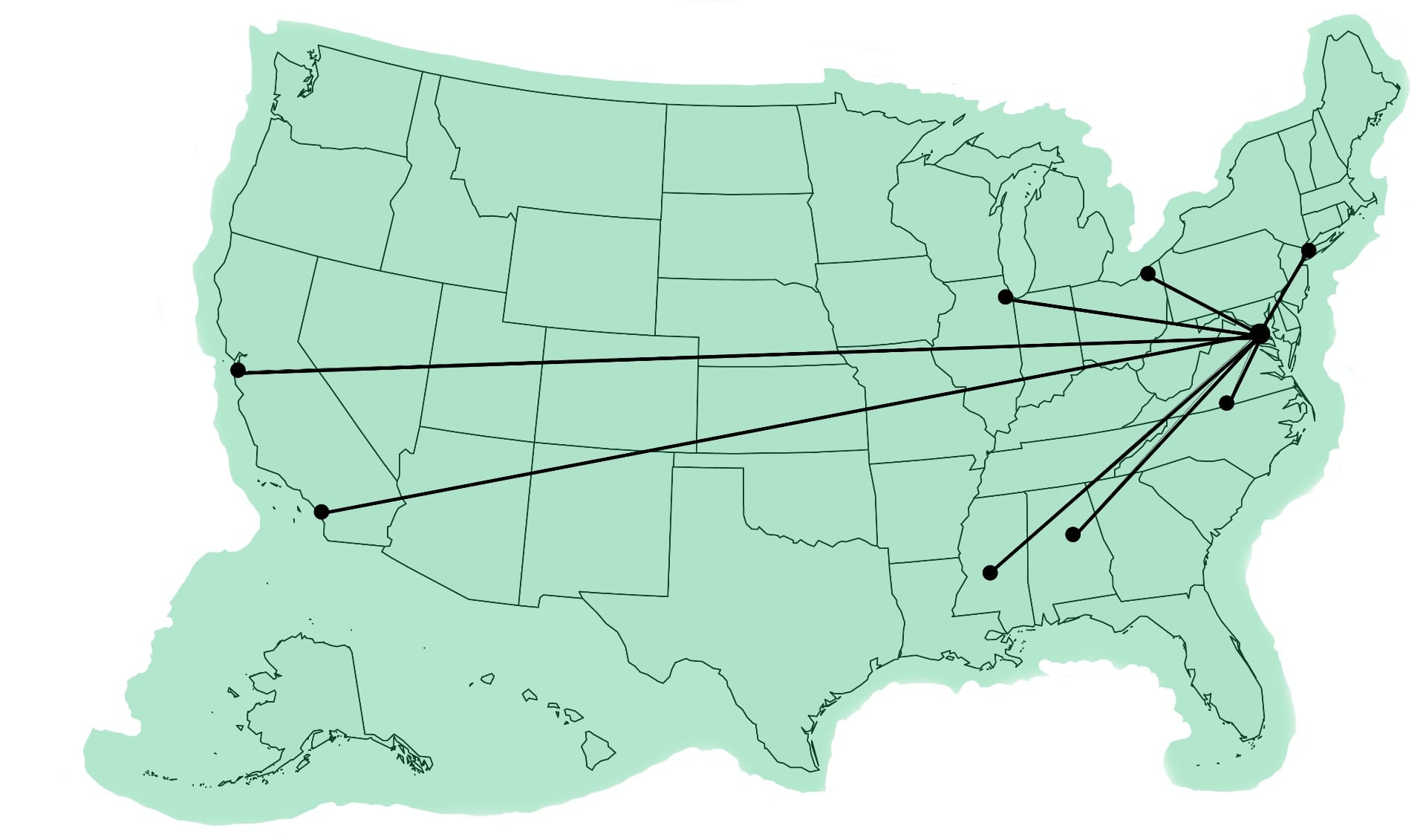

A map of the American cities that figure into The March. Map by Tom Fischer.

The March depicts preparations for the historic March on Washington as they took place all over the United States in the days leading up to the event.

Washington, D.C.

The March on Washington took place in Washington, D.C., the nation’s capital. In addition to the March, several other important events pertaining to the demonstration took place in this city. Press conferences, church gatherings, and more filled the days before and after the March on Washington. Conversations after James Blue’s The March was released took place in the White House.

New York, New York

New Yorkers contributed massive amounts of people, resources, and organizational assistance to help make the March on Washington happen. Volunteers worked around the clock to prepare sandwiches for as many of the marchers as they could. Blue claims they made nearly 80,000 lunches to send with marchers from the city. The New York City branch of the National Council of Churches was a major contributor to the success of the movement.

Birmingham, Alabama, and Jackson, Mississippi

Among other cities, Blue mentions that marchers came from Birmingham and Jackson. These cities’ distance to Washington is equated to the distance between Johannesburg, South Africa, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to give international viewers better perspective on how far marchers traveled.

Bethesda, Maryland

The opening scenes of The March show a large contingent from Bethesda, Maryland, who have gathered before marching. The footage was taken in Bethesda prior to the March on Washington.

Danville, Virginia

Marchers from Danville, Virginia, are shown having arrived in Washington the night before the March. The Reverend Lawrence Campbell from Bibleway Church in Danville, Virginia, can be heard over marchers as they prepare for the next day. Founded in 1957, Bibleway serves as a source of missionary outreach and community engagement, and it has grown into the parent church of an international network of Christian churches. Danville was the site of violent episode in the history of the Civil Rights Movement. On June 10, 1963, sixty high school students who had marched to the Danville’s municipal building to protest segregation were met with police who used high-pressure hoses and nightsticks on them.

Chicago, Illinois

Chicago is mentioned in connection to Cleveland, Ohio, as both are roughly the same distance to Washington as Buenos Aires, Argentina, is to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. James Blue made comparisons like this to help international viewers grasp the long distances that marchers traveled.

Los Angeles, California

Several scenes in The March show Reverend Edward S. Williams of Los Angeles, California, preaching to his congregation at Holman United Methodist Church. Holman UMC was founded in 1945 to serve the Black community of Los Angeles, and it is still active in community outreach to this day.

Cleveland, Ohio

Several marchers came from Cleveland, Ohio, which also happened to be the main headquarters of the National Council of Churches in the United States. The National Council provided the choir and personnel from New York City.

San Francisco, California

In his narration in The March, James Blue mentions San Francisco along with Los Angeles, California, as examples of how far marchers traveled to reach Washington, DC. He compares the distance between California and DC to the distance between Moscow, Russia, and Bombay (Mumbai), India.

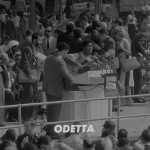

Music

Aside from Blue’s narration and King’s “I Have A Dream” speech, much of the dialogue in The March takes the form of song. In addition to performances by well-known musicians at the March on Washington itself, Blue depicts marchers from all over the country raising their voices in song as they make their way to Washington.

Below, you can learn more about two of the songs in The March and browse the full lyrics of all the songs in the film.

“Keep Your Eyes on the Prize”

The spiritual “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize” has a rich history within the civil rights era despite relative obscurity compared to spirituals like “We Shall Overcome.” The song was originally known as “Gospel Plow” and “Hold On” before being reworked by civil rights activist and musician Alice Wine in the 1950s. The musical structure of “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize” can take several forms, as is common for spirituals. Traditionally, the first part of each verse is sung by a leader, with the second half (“keep your eyes on the prize / hold on, hold on”) sung in response by the chorus. Alternatively, the leader may sing the entire piece with the chorus echoing each time the leader sings “hold on,” joining in wherever they feel comfortable. This flexibility allows groups of all expertise levels to learn the song without too much work. The version sung in The March includes a verse about the FBI investigating hate crimes against African American citizens. Improvised lyrics are also quite common when singing spirituals, and thus it is no surprise that the leader of the marchers includes a verse relevant to current events.

The placement of this spiritual at the beginning of the documentary has several implied messages. Young men and women turn side to side learning what comes next and listening to the sounds being made. One watches as individuals gradually learn the song from others around them. This scene is like a summary of the events leading into the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom; individual groups reach out, communicate, and learn to speak together with one voice.

In addition to this, the original lyrics of the piece speak to those who are persecuted, discriminated against, and oppressed. The opening phrase, “Paul and Silas bound in jail,” refers to the Biblical apostles Paul and Silas, who were imprisoned for preaching Christianity. The symbol of the Gospel Plow is also important to this spiritual. It refers to the holy work of those seeking what is good and right. These allusions in context of The March highlight the buildup and hard work that culminates in the March on Washington, framing the speech by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., as a metaphorical earthquake that will “shake the chains” of oppression off all who march for freedom.

“We Shall Overcome”

“We Shall Overcome” is perhaps the most iconic spiritual of the civil rights movement, quickly becoming the anthem of marchers, protesters, and activists worldwide. The song itself is incredibly easy to teach to new singers, which may contribute to its popularity. “Verses” consist of a repeated phrase of no more than 5 syllables. In terms of range, the song sits quite comfortably on the voice, meaning even the least confident singer can manage this song. The slow tempo also allows leaders to announce the words of the upcoming verse, which makes the piece amenable to improvised lyrics.

Activists Zilphia Horton and Pete Seeger promoted the song in their own time. Horton was a folk culture specialist and activist who learned the song while picketing with tobacco farm laborers. After adding verses and changing a few of the words, Horton taught the piece to acclaimed folk musician Pete Seeger. Seeger is credited with the changing “we will overcome” to “we shall overcome,” the lyrics popularized today.

“We Shall Overcome” is featured nearly six times in The March, all in different contexts: from marchers singing in the night to gospel choirs singing in harmony, a rich array of vocalists lend their voices to Blue’s film. The recurring use of this song makes sense as the intended international audience would instantly recognize this quintessential piece of music. Blue also uses this piece to exemplify how firmly united the marchers are even with such diversity. Cameras swivel left and right to show massive crowds all holding hands and belting the song at the top of their voice while marching, contrasted with close-ups on choir members singing delicately during preparatory activities. No matter their race, gender, place of origin, or class, every single person in The March clearly knows this song well. In the last minutes of The March, “We Shall Overcome” plays in several layers: the marchers sing together, an organ is superimposed over the film, and vocalist Geraldine Anderson is featured. Blue does this to musically represent the overwhelming, overlapping emotions after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speech. The song becomes more insistent with the renewed energy of the marchers: they shall overcome, and someday is looking closer and closer.